There is a piece of wisdom from avant garde composer, John Cage, which goes something like this: if something is done for 2 minutes and it seems boring, try it for 4 minutes. If 4 is boring then try 8. If 8 is boring, then 16, etc. Eventually it will become interesting. This is an intriguing strategy from one of the 20th century's primary music thinkers. Often it is thought in many circles that less is more. But, sometimes, more is more and less is just, well, less. As a thinker myself, who also happens to be musical, ideas are an important currency. Recently, I've become very stagnated. I long to try other musical directions that I am simply unable to follow - primarily for financial reasons. I also feel that I've become stuck and am no longer content to repeat myself. In the last three months I have developed mostly longer pieces of 15-20 minutes in length. This has been rewarding and useful to me. They will forever be known as my "Berlin School" months. But there is only so many times you can repeat the trick. A thinker must always be moving on. Ideas get past their sell by date.

One constant thorn in the side when making music is the thorny subject of genre. I have never really set out to make music to fit a pre-existing genre. Or, at least, when I have it has always been the worst thing possible that has been produced. I mean total disaster. I understand that people have a need to categorise and classify things. Order of this kind seems to be a basic human need. But it can become lazy. Such a kind of order is also an open invitation to the iconoclastic or contrarian to refuse to fit in and to disappear somewhere between the cracks of classification. But, you will be saying, your most recent music is "Berlin School" and that is a genre. Yes, it is. But I didn't set out "to make some Berlin School". I'd been listening to it and kind of fell into it. The problem then is, of course, that you read the music is Berlin School and, since you don't like music you regard as Berlin School, you decide to totally ignore that music of mine. The classification has become a reason to exclude whole swathes of music (or art, or literature, or films, or whatever).

Matters of taste like this occur to us all every day. And, I must say, I don't like it. But I might as well sit on the shore and command the sea not to come in because no one can do anything about it. Taste is a given in life. Everyone has it and no one is in control of it. You do not sit there and decide your tastes by some deliberate process of reasoning. It just occurs to you that you like something or you don't. At no point is this a process you control. Its almost mystical. It follows that, since none of this is deliberate, you can neither take credit for, or be blamed for, your tastes. You like what you like and there is nothing more to say about it. I'm sure we all get caught up in scenarios where someone we know likes something we hate. I know just how annoying that can feel. You get caught up in it. But its really irrational and stupid to do so. No one deliberately chose their tastes. Of course, you can cultivate and explore certain tastes. But, more often than not, that just leads you on to other tastes and, sometimes, you even surprise yourself in the things you come to like and dislike.

My model human being in this respect, my ideal, is the "taste explorer". This is a person who is prepared to put their tastes to the test and try out new things, someone who is not prepared to be spoon fed whatever comes off the mainstream conveyor belt today. This is the opposite of a grazer. This is a person who not only goes outside and looks around but he, or she, actually turns over some rocks to see what is hiding underneath. Now, as we all know, nasty creepy crawlies lurk under rocks. But sometimes that can be interesting too. And, as I have grown older, I've learnt that life is not about clinging to the things you like and avoiding at all costs the things you don't. In fact (this is an open secret) you can often learn more from the things you don't like than from the things that you do. Tastes can serve a purpose and it is good to explore them and test them.

I come to this subject by way of the English comedian Stewart Lee. Lee is a comedian who openly embraces political correctness and is concerned to cultivate a certain image of disdain for the mainstream. (I should add that I'm a relatively recent fan of his act but would question a number of his personal beliefs.) He seems to glory in his love of obscure art of different kinds (including music). This quite often annoys his critics who berate and insult him for this obscurantist snobbishness. I was reading an interview with Lee from earlier in the year online and in it he referred to many musical acts I had never heard of and referred, as well, to what he regarded as his favourite album of all time, Hex Enduction Hour, a 1982 album by the British Art Punk band, The Fall. Unfortunately, in the same interview, he offhandedly referred to British Metal band, Iron Maiden, as "awful". Now I like Iron Maiden. I didn't like them at first but through exposure to them, thanks to a brother with a bedroom next door to mine, I grew to like them and still do to this day 30 years later. In contrast, until about 5 hours ago I had never once heard anything by The Fall (although I had heard lead singer, Mark E Smith, on a single by Inspiral Carpets).

Reading Lee's casual dismissal of Iron Maiden, a band beloved by not a small number of people worldwide and one with a legendary dedication to giving their fans value for money, I felt sad. I wondered why people have to dismiss things in such a way and mused that more often than not this is indicative of a casual judgment thrown out without any deep knowledge of the subject. I went for a walk and thought about it some more. Now, in the light of what I've already said, its very likely that Lee does not control whether he likes Iron Maiden or not. Do I control the fact I like them anymore than the fact he doesn't? No. So all this is silly. Its just matters of taste. We all have taste and none of us really control what we like. Stop being silly. But I did determine to do one thing to dignify the process a little of liking something or not. I determined that I would listen to Hex Enduction Hour by The Fall and come to some conclusion about it. And so I did. Now in my brain there was lodged some horrifically brief judgment on The Fall as "tuneless noise". I have no idea on what this notional judgment was based but I suspect it was based on my appraisal of the kinds of people who seem to like The Fall. (I have similar intuitions about people who like The Smiths or U2 whilst being more familiar with their work.) Whatever. That is now lost in the mists of time. But I listened. And it wasn't bad at all. Indeed, some of it I liked. I read that Mark E Smith, who is really all The Fall is, was a fan of Can, the German Krautrock band. The album I listened to was really an arty, punky Manchester, England version of that. So I challenged my tastes and my preconceptions and the sky didn't fall (!) in.

This all just makes me muse even more on the question of taste. I think that the question of what anyone's tastes are really ends up being an irrelevant one. The more pertinent focus is whether those tastes are static or movable, whether someone is open to new things or closed-minded. I have an online contact who makes music and he goes under the moniker of "Iceman Bob". I want to finish this article by saying a bit about his latest album "Magic City" in this regard.

I've been listening to Bob's music for a while. It isn't mainstream. It often isn't pretty. I'd even go as far as saying that sometimes I really don't like what I'm listening to. But, nevertheless, I persevere with it because there is something about Bob's music that is more important than petty questions of like and dislike. So often, as I hinted above, we like or dislike something based on the pigeon hole we think it fits in. Based on that judgment, we classify it as of interest or as something to forget about. The thing is, with Bob there really is no pigeon hole to fit his music into. Not only do I not know much about him but, from listening to the music itself, its really hard to tell what, if any, influences are behind it. Magic City is a prime example of this. It seems somehow sui generis, in a class of its own. It demands to be listened to not as an example of some genre but on its own terms. And I really like things like that. Such things demand to be listened to because here we have something new, something different. Its fair to say that if this album was easily classified as this or that I'd just ignore it. But it isn't and so I didn't.

Magic City, like all of Bob's albums, makes use of drums, synths and guitars. Often Bob seems happy to lay down some backing track and then play his various guitars over the top at random, performing a sort of crazy jazz-rock wandering. This is often uplifting to my ears. (His track "Garuda" from the album "New Directions" is one of my all time favourites in this respect.) That said, his lead electric guitar tone really does annoy me and I wish he would do more to vary it. Maybe this is an area he might concentrate on in the future, who knows? Or maybe he likes the sound he makes now? Its his choice at the end of the day. Anyway, this is a matter of personal taste and we have already covered that in this article. For the most part, Magic City uses a larger array of sounds than his previous albums and I welcome this. This album seems more experimental and imbued with a spirit of adventure and interest which kept me listening from start to finish without ever once having the urge to bail.

Overall, I was astounded listening to this album which, like most of Bob's work, isn't short. Here we have 11 tracks that are on average each 11 or 12 minutes long. So its close on 2 hours of music here. On Magic City Bob has shaken things up a little. He's not content to stick to a formula and churn out 11 variations of the same thing and I was happy to hear that (filtering my own issues of stagnation into my thinking, of course). "Consecration of the Ordinary", the first track, was especially different, making use of speech, amongst other things. The album was at times a very difficult listen but I regard that as no bad thing. More and more I am drawn to music that requires you be challenged to listen to it and asks you to measure yourself against it. I'm not sure this is Bob's intention. I think he is just doing what comes naturally and having fun. Fair enough. But I would say the music he produces is challenging and requires listeners that are up to the task of listening to it. If you want to go back to the lazy classifications I think Magic City would fit comfortably alongside a number of the German "Space Rock" or Kosmische albums of the early 1970s. That's the content of the music as well as the title, by the way. Being that I have recently been studying this body of work quite heavily, it was edifying to find similar music being made in Montana by an American in 2015.

In the end, I wouldn't recommend Magic City to everyone. Its far from mainstream and is really the musical explorations of a very interesting man. If you like German rock of the early 1970s you may be more inclined to like it but that is no guide. But, then again, as I've already said, its not so much about whether you might like this album or not but whether you are prepared to challenge your tastes and be opened up to new experiences. If so, Magic City would be a great challenge indeed.

You can hear Magic City by Iceman Bob HERE!

Monday, 30 March 2015

Matters of Taste

Labels:

context,

Iceman Bob,

Iron Maiden,

kosmische,

krautrock,

Magic City,

meaning,

Stewart Lee,

taste,

tastes,

The Fall

Sunday, 22 March 2015

Are Human Beings Robots?: Our True Place in the Cosmos

I've spent the last several days thinking about robots and artificial intelligence. It seems there are quite a few people who are interested in this subject too. But my mind has wandered, as it is apt to do. (Question: do we control our minds or do our minds control us? Its not as easy to answer as you might think.) I found myself reading about cosmology and evolution to satiate a wide-ranging interest in humanity and what makes us, us. So this blog is going to kind of straddle the two stools of robots and the universe and probably do neither any justice at all. These blogs are just me thinking out loud, ok?

Last night I watched both the original Tron (which I had never seen aside from snippets) and Tron: Legacy (which I had seen once before). Both films are ostensibly about intelligent computer programs. 1982's original Tron was strangely compelling as a film. Its terribly out of date graphics and style was appealing and in a way that the sequel's weren't. Better does not always mean better it seems. There was something about the way the light cycle races in the original were better than the newer version. And the sound design in the original was much better (and it was Oscar nominated). But I digress into film criticism.

Both films, as I say, are set in computer worlds. It doesn't seem that there was much thought behind the setup though. Its simply a way to make a film about computers and programs. I have found, as I've watched films about computers and robots this week, that there is usually some throw away line somewhere about a robot or computer being "just a computer" or "just a robot" and "it can't think". It seems that at the conscious level "thinking" is taken to be a marker that shows how intelligent computers or robots are not like we humans. But this seems strange to me. Reasoning is surely a marker of something that makes us stand out in the animal kingdom. However, if anything could calculate then surely that's exactly the one thing that a computer or intelligent robot would be good at? But are thinking and reasoning and calculating all the same thing? Thinking clearly occurs in a number of different ways. There is not just logical reasoning or solving a problem. These kinds of things you could surely teach a computer to do very well at. (I recall to mind that a computer did beat Grand Master Gary Kasparov at chess.) There is also imaginative thinking and how good might an artificial intelligence be at that?

In thinking about this I come back to biology. Human beings are biological organisms. A computer or robot will never have to worry about feeling sick, needing to go to the toilet or having a tooth ache. It will never feel hot and need to take its jumper off. It will never need to tie shoes to its feet so that it can travel somewhere. This matters because these trivialities are the conditions of human life. Of course, you can say that computers may overheat or malfunction or a part may wear out. But are these merely analogous things or direct comparisons? I think it matters if something is biological or not and I think that makes a difference. Human beings feel things. They have intuitions that are only loosely connected to reasoning ability. They can be happy and they can be afraid. These things have physical, biological consequences. I think of Commander Data from Star Trek who was given an "emotion chip" that his creator, Dr Soong, made for him. When it was first put in Data briefly went nuts and it overloaded his neural net. Quite. But more than that, it melded to his circuits so that it couldn't be removed. By design. It seems the inventor in this fictional story rightly saw that emotions cannot be added and taken away at someone's discretion. If you have them, you have them. And you have to learn to live with them. That is our human condition and that is what the character Commander Data had to learn. So human beings cannot be reduced to intelligent functions or reasoning power. These things are as much human as the fact that every once in a while you will need to cut your toe nails.

In addition to all this thinking about intelligent robots in the past few days I was also thinking about the universe, a fascinating subject I have spent far too little of my 46 years thinking about. I have never really been a "science" person. If we must have a divide then I have definitely been on the side of "art". But that's not to say that scientific things couldn't interest me. They have just never so far been presented in a way as to make them palatable for me. All too often science has been presented as "scientism", offering a one-size-fits-all approach to everything that matters. Basically, scientism is the belief that science is all that matters, the highest form of human thinking. Not surprisingly, being an artistic character, I found this an arrogant assumption and rejected it outright. Science and scientists can get stuffed!

But its also true that the things you find out for yourself are the things that stick with you for longer. I am a curious person and am able to do research. So on Friday I was looking at articles about the Earth and the universe. I read things about our sun (thanks partial eclipse!) and how long it was going to last for (a few billion years yet) and then migrated to grand narratives about how our planet had been formed and what it was thought would happen to it in the future. Its fascinating to read the myriad ways in which bad things will happen to the planet you are living on. I came away from this reading with the sense that human beings are a speck in the universe or, as George Carlin once put it in one of his acts, a "surface nuisance". The show to which I refer was notable for a skit he did on environmentalists who, says Carlin, are "trying to save the planet for their Volvos". He ran through a list of things that have already happened to the Earth long before our species arrived and the upshot of his skit was that nothing we do makes any real difference to this planet in the grand scheme of things. Its human arrogance to think that we have that kind of ability. I have some sympathy with this view.

(Watch George Carlin's Environment skit here)

Put simply, most human beings hold to what is called by the British paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, Henry Gee, "Human Exceptionalism". This is the view that human beings are essentially different to all other animals, if not all other living things in the universe. Its often accompanied by the belief that we are somehow the pinnacle of nature - as if evolution was always aiming to get to us, the zenith of the process. Put simply, humans are better. But as Gee, also a senior editor at the science journal, Nature, points out, to even think such a thing is to completely misunderstand the theory of evolution, a process which retrospectively describes human observations about the development of life rather than some force working in the universe with a predisposition or purpose to create human beings. The problem is that we are people. We see through human eyes and we cannot put those eyes aside to see in any other way. The forces that created us equipped us with egos for the purposes of self-preservation and even those of us with low self-esteem (such as myself) still regard ourselves as important. But imagine looking at yourself through an impossibly powerful telescope from somewhere a billion galaxies away. How important would you be then? You wouldn't even register. Even our planet would be a speck, one of billions.You wouldn't catch an intelligent robot having such ideas above its station - except in a film where it was basically standing in for a human being! Skynet and the revolt of the machines is a uniquely human kind of story. All we think and imagine is. We are, after all, only human. But what kind of stories would intelligent robots tell?

So I learn that I am just another human, one of a species of puffed up individuals that happened to evolve on a meaningless planet located at Nowheresville, The Universe. I'm on the third planet of a solar system that in a few billion years will be thrown into chaos when it's star has burnt up all its hydrogen and begins to change from a bright burning star into a Red Giant. At that point it will expand to such a degree that Mercury, Venus, and likely Earth as well, will be consumed. Long before that our planet will have become too hot to support life (the sun's luminosity is, and has been, increasing for millions of years) and will likely have been hit by several asteroids of considerable size that cause extinction events on Earth. Scientists already tell us that there have been at least 5 "great extinction events" on the earth before now. In 50 million years the Canadian Rockies will have worn away and become a plain. In only 50,000 years the Niagara Falls will no longer exist, having worn away the river bed right back the 32 kilometers to Lake Erie. Not that that will matter as by the time those 50,000 years have past we will be due for another glacial period on Earth. Seas will freeze and whole countries will be under metres of ice. In 250 million years plate tectonics dictate that all the continents will have fused together into a super continent, something that has likely happened before. In less than 1 billion years it is likely that carbon dioxide levels will fall so low that photosynthesis becomes impossible leading to extinctions of most forms of life. These things are not the scare-mongering of those with environmental concerns. They are not based on a humanistic concern with how our tiny species is affecting this planet. They are the science of our planet. You see, when you choose not to look with egotistical human eyes, eyes that are always focused on the here and now, on the pitifully short time span that each of us has, you see that everything around us is always moving and always changing. Change, indeed, is the constant of the universe. But you need eyes to see it.

The year 1816 (only 199 years ago) was known as "The Year Without A Summer". It was called that because there were icy lakes and rivers in August and snow in June. Crops failed. People starved. This was in the Northern Hemisphere (Europe and North America). It was caused by a volcanic eruption not in the Northern Hemisphere but in the Southern Hemisphere, specifically at Mount Tambora in what is now Indonesia in 1815. It caused what is called a "volcanic winter". The eruption has been estimated to be the worst in at least the last 1,300 years. What strikes me about this, in my "trying to see without human eyes" way of thinking, is that 1,300 years is not very long. Indeed, time lasts a lot longer in the natural world than we humans have been given the ability to credit. We zone out when the numbers get too big. We are programmed to concentrate on us and what will affect us and ours (like a robot?!). The good news, though, is that because all of us live such pathetically small lives its likely stuff like this won't happen to us. But on the logic of the universe these things surely will happen. Far from us humans being the masters of our destiny, we are are helpless ants in the ant hill just waiting for the next disaster to strike. Like those ants, we are powerless to stop it, slaves to forces we can neither comprehend nor control. As Henry Gee puts it in terms of scientific discovery, "every time we learn something, we also learn that there is even more we now know we don't know".

So maybe there is a way in which we are like robots. We are dumb before the things that created us, powerless to affect or control what happens to us (in the grand scheme of things). It makes you think.

For more doomsday scenarios (real ones, based in scientific thinking) check out the articles Timeline of the Far Future and Future of the Earth

You can listen to my music at elektronischeexistenz.bandcamp.com

Last night I watched both the original Tron (which I had never seen aside from snippets) and Tron: Legacy (which I had seen once before). Both films are ostensibly about intelligent computer programs. 1982's original Tron was strangely compelling as a film. Its terribly out of date graphics and style was appealing and in a way that the sequel's weren't. Better does not always mean better it seems. There was something about the way the light cycle races in the original were better than the newer version. And the sound design in the original was much better (and it was Oscar nominated). But I digress into film criticism.

Both films, as I say, are set in computer worlds. It doesn't seem that there was much thought behind the setup though. Its simply a way to make a film about computers and programs. I have found, as I've watched films about computers and robots this week, that there is usually some throw away line somewhere about a robot or computer being "just a computer" or "just a robot" and "it can't think". It seems that at the conscious level "thinking" is taken to be a marker that shows how intelligent computers or robots are not like we humans. But this seems strange to me. Reasoning is surely a marker of something that makes us stand out in the animal kingdom. However, if anything could calculate then surely that's exactly the one thing that a computer or intelligent robot would be good at? But are thinking and reasoning and calculating all the same thing? Thinking clearly occurs in a number of different ways. There is not just logical reasoning or solving a problem. These kinds of things you could surely teach a computer to do very well at. (I recall to mind that a computer did beat Grand Master Gary Kasparov at chess.) There is also imaginative thinking and how good might an artificial intelligence be at that?

In thinking about this I come back to biology. Human beings are biological organisms. A computer or robot will never have to worry about feeling sick, needing to go to the toilet or having a tooth ache. It will never feel hot and need to take its jumper off. It will never need to tie shoes to its feet so that it can travel somewhere. This matters because these trivialities are the conditions of human life. Of course, you can say that computers may overheat or malfunction or a part may wear out. But are these merely analogous things or direct comparisons? I think it matters if something is biological or not and I think that makes a difference. Human beings feel things. They have intuitions that are only loosely connected to reasoning ability. They can be happy and they can be afraid. These things have physical, biological consequences. I think of Commander Data from Star Trek who was given an "emotion chip" that his creator, Dr Soong, made for him. When it was first put in Data briefly went nuts and it overloaded his neural net. Quite. But more than that, it melded to his circuits so that it couldn't be removed. By design. It seems the inventor in this fictional story rightly saw that emotions cannot be added and taken away at someone's discretion. If you have them, you have them. And you have to learn to live with them. That is our human condition and that is what the character Commander Data had to learn. So human beings cannot be reduced to intelligent functions or reasoning power. These things are as much human as the fact that every once in a while you will need to cut your toe nails.

In addition to all this thinking about intelligent robots in the past few days I was also thinking about the universe, a fascinating subject I have spent far too little of my 46 years thinking about. I have never really been a "science" person. If we must have a divide then I have definitely been on the side of "art". But that's not to say that scientific things couldn't interest me. They have just never so far been presented in a way as to make them palatable for me. All too often science has been presented as "scientism", offering a one-size-fits-all approach to everything that matters. Basically, scientism is the belief that science is all that matters, the highest form of human thinking. Not surprisingly, being an artistic character, I found this an arrogant assumption and rejected it outright. Science and scientists can get stuffed!

But its also true that the things you find out for yourself are the things that stick with you for longer. I am a curious person and am able to do research. So on Friday I was looking at articles about the Earth and the universe. I read things about our sun (thanks partial eclipse!) and how long it was going to last for (a few billion years yet) and then migrated to grand narratives about how our planet had been formed and what it was thought would happen to it in the future. Its fascinating to read the myriad ways in which bad things will happen to the planet you are living on. I came away from this reading with the sense that human beings are a speck in the universe or, as George Carlin once put it in one of his acts, a "surface nuisance". The show to which I refer was notable for a skit he did on environmentalists who, says Carlin, are "trying to save the planet for their Volvos". He ran through a list of things that have already happened to the Earth long before our species arrived and the upshot of his skit was that nothing we do makes any real difference to this planet in the grand scheme of things. Its human arrogance to think that we have that kind of ability. I have some sympathy with this view.

(Watch George Carlin's Environment skit here)

Put simply, most human beings hold to what is called by the British paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, Henry Gee, "Human Exceptionalism". This is the view that human beings are essentially different to all other animals, if not all other living things in the universe. Its often accompanied by the belief that we are somehow the pinnacle of nature - as if evolution was always aiming to get to us, the zenith of the process. Put simply, humans are better. But as Gee, also a senior editor at the science journal, Nature, points out, to even think such a thing is to completely misunderstand the theory of evolution, a process which retrospectively describes human observations about the development of life rather than some force working in the universe with a predisposition or purpose to create human beings. The problem is that we are people. We see through human eyes and we cannot put those eyes aside to see in any other way. The forces that created us equipped us with egos for the purposes of self-preservation and even those of us with low self-esteem (such as myself) still regard ourselves as important. But imagine looking at yourself through an impossibly powerful telescope from somewhere a billion galaxies away. How important would you be then? You wouldn't even register. Even our planet would be a speck, one of billions.You wouldn't catch an intelligent robot having such ideas above its station - except in a film where it was basically standing in for a human being! Skynet and the revolt of the machines is a uniquely human kind of story. All we think and imagine is. We are, after all, only human. But what kind of stories would intelligent robots tell?

So I learn that I am just another human, one of a species of puffed up individuals that happened to evolve on a meaningless planet located at Nowheresville, The Universe. I'm on the third planet of a solar system that in a few billion years will be thrown into chaos when it's star has burnt up all its hydrogen and begins to change from a bright burning star into a Red Giant. At that point it will expand to such a degree that Mercury, Venus, and likely Earth as well, will be consumed. Long before that our planet will have become too hot to support life (the sun's luminosity is, and has been, increasing for millions of years) and will likely have been hit by several asteroids of considerable size that cause extinction events on Earth. Scientists already tell us that there have been at least 5 "great extinction events" on the earth before now. In 50 million years the Canadian Rockies will have worn away and become a plain. In only 50,000 years the Niagara Falls will no longer exist, having worn away the river bed right back the 32 kilometers to Lake Erie. Not that that will matter as by the time those 50,000 years have past we will be due for another glacial period on Earth. Seas will freeze and whole countries will be under metres of ice. In 250 million years plate tectonics dictate that all the continents will have fused together into a super continent, something that has likely happened before. In less than 1 billion years it is likely that carbon dioxide levels will fall so low that photosynthesis becomes impossible leading to extinctions of most forms of life. These things are not the scare-mongering of those with environmental concerns. They are not based on a humanistic concern with how our tiny species is affecting this planet. They are the science of our planet. You see, when you choose not to look with egotistical human eyes, eyes that are always focused on the here and now, on the pitifully short time span that each of us has, you see that everything around us is always moving and always changing. Change, indeed, is the constant of the universe. But you need eyes to see it.

The year 1816 (only 199 years ago) was known as "The Year Without A Summer". It was called that because there were icy lakes and rivers in August and snow in June. Crops failed. People starved. This was in the Northern Hemisphere (Europe and North America). It was caused by a volcanic eruption not in the Northern Hemisphere but in the Southern Hemisphere, specifically at Mount Tambora in what is now Indonesia in 1815. It caused what is called a "volcanic winter". The eruption has been estimated to be the worst in at least the last 1,300 years. What strikes me about this, in my "trying to see without human eyes" way of thinking, is that 1,300 years is not very long. Indeed, time lasts a lot longer in the natural world than we humans have been given the ability to credit. We zone out when the numbers get too big. We are programmed to concentrate on us and what will affect us and ours (like a robot?!). The good news, though, is that because all of us live such pathetically small lives its likely stuff like this won't happen to us. But on the logic of the universe these things surely will happen. Far from us humans being the masters of our destiny, we are are helpless ants in the ant hill just waiting for the next disaster to strike. Like those ants, we are powerless to stop it, slaves to forces we can neither comprehend nor control. As Henry Gee puts it in terms of scientific discovery, "every time we learn something, we also learn that there is even more we now know we don't know".

So maybe there is a way in which we are like robots. We are dumb before the things that created us, powerless to affect or control what happens to us (in the grand scheme of things). It makes you think.

For more doomsday scenarios (real ones, based in scientific thinking) check out the articles Timeline of the Far Future and Future of the Earth

You can listen to my music at elektronischeexistenz.bandcamp.com

Labels:

being,

death,

exceptionalism,

existence,

existentialism,

human,

humanity,

life,

meaning,

robots,

science,

science fiction,

the universe

Friday, 20 March 2015

Would You Worry About Robots That Had Free Will?

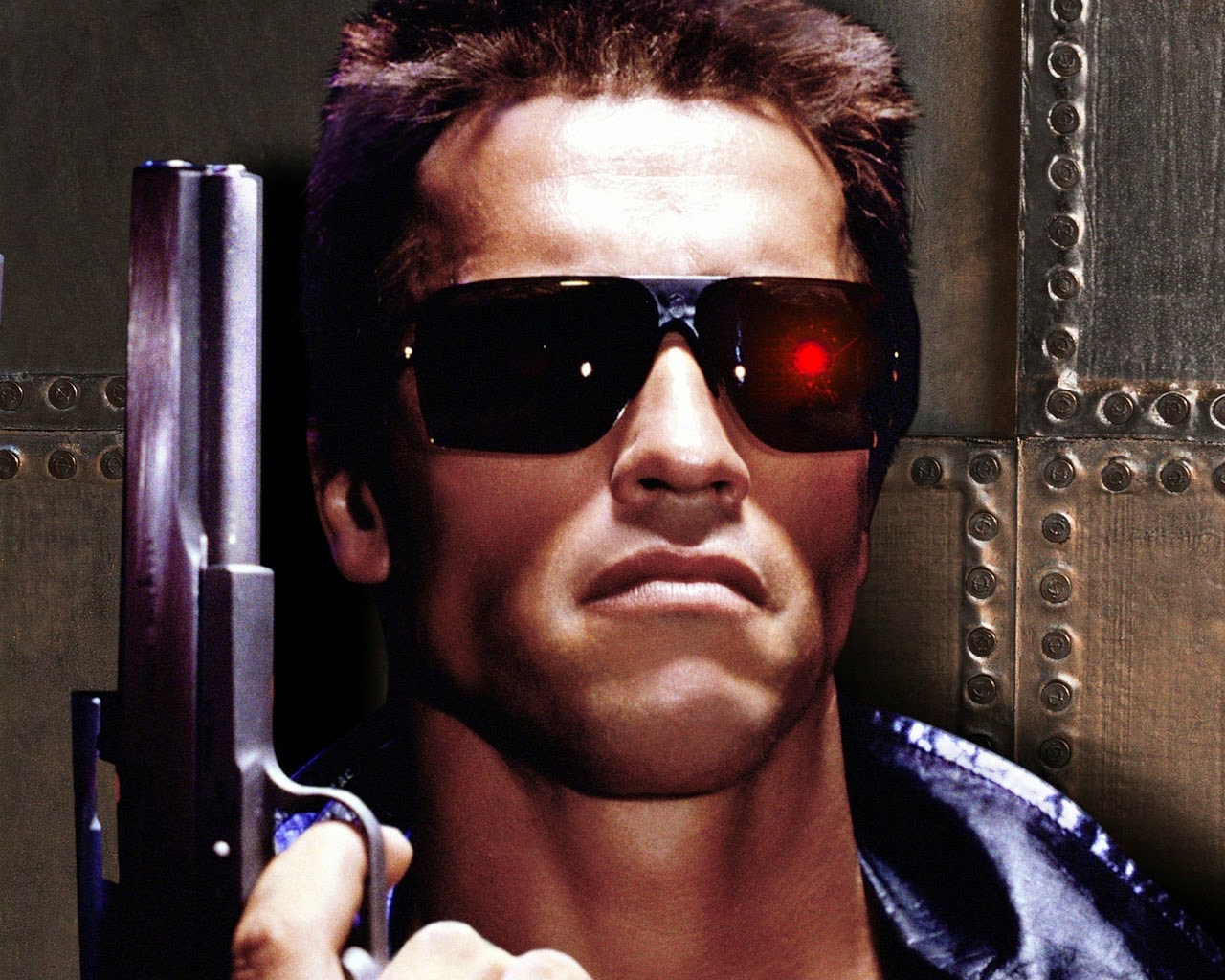

Its perhaps a scary thought, a very scary thought: an intelligent robot with free will, one making up the rules for itself as it goes along. Think Terminator, right? Or maybe the gunfighter character Yul Brynner plays in "Westworld", a defective robot that turns from being a fairground attraction into a super intelligent robot on a mission to kill you? But, if you think about it, is it really as scary as it seems? After all, you live in a world full of 7 billion humans and they (mostly) have free will as well. Are you huddled in a corner, scared to go outside, because of that? Then why would intelligent robots with free will be any more frightening? What are your unspoken assumptions here that drive your decision to regard such robots as either terrifying or no worse than the current situation we find ourselves in? I suggest our thinking here is guided by our general thinking about robots and about free will. It may be that, in both cases, a little reflection clarifies our thinking once you dig a little under the surface.

Take "free will" for example. It is customary to regard free will as the freedom to act on your own recognisance without coercion or pressure from outside sources in any sense. But, when you think about it, free will is not free in any absolute sense at all. Besides the everyday circumstances of your life, which directly affect the choices you can make, there is also your genetic make up to consider. This affects the choices you can make too because it is responsible not just for who you are but who you can be. In short, there is both nature and nurture acting upon you at all times. What's more, you are one tiny piece of a chain of events, a stream of consciousness if you will, that you don't control. Some people would even suggest that things happen the way they do because they have to. Others, who believe in a multiverse, suggest that everything that can possibly happen is happening right now in a billion different versions of all possible worlds. Whether you believe that or not, the point is made that so much more happens in the world every day that you don't control than the tiny amount of things that you do.

And then we turn to robots. Robots are artificial creations. I've recently watched a number of films which toy with the fantasy that robots could become alive. As Number 5 in the film Short Circuit says, "I'm alive!". As creations, robots have a creator. They rely on the creator's programming to function. This programming delimits all the possibilities for the robot concerned. But there is a stumbling block. This stumbling block is called "artificial intelligence". Artificial Intelligence, or AI, is like putting a brain inside a robot (a computer in effect) which can learn and adapt in ways analogous to the human mind. This, it is hoped, allows the robot to begin making its own choices, developing its own thought patterns and ways of choosing. It gives the robot the ability to reason. It is a very moot point, for me at least, whether this would constitute the robot as being alive, as having a consciousness or as being self-aware. And would a robot that could reason through AI therefore have free will? Would that depend on the programmer or could such a robot "transcend its programming"?

Well, as I've already suggested, human free will it not really free. Human free will is constrained by many factors. But we can still call it free because it is the only sort of free will we could ever have anyway. Human beings are fallible and contingent beings. They are not gods and cannot stand outside the stream of events to get a view that wasn't a result of them or that will not have consequences further on down the line for them. So, in this respect, we could not say that a robot couldn't have free will because it would be reliant on programming or constrained by outside things - because all free will is constrained anyway. Discussing the various types of constraint and their impact is another discussion though. Here it is enough to point out that free will isn't free whether you are a human or an intelligent robot. Being programmed could act as the very constraint which makes robot free will possible, in fact.

It occurs to me as I write out this blog that one difference between humans and robots is culture. Humans have culture and even many micro-cultures and these greatly influence human thinking and action. Robots, on the other hand, have no culture because these things rely on sociability and being able to think and feel for yourself. Being able to reason, compare and pass imaginative, artistic judgments are part of this too. Again, in the film Short Circuit, the scientist portrayed by actor Steve Guttenberg refuses to believe that Number 5 is alive and so he tries to trick him. He gives him a piece of paper with writing on it and a red smudge along the fold of the paper. He asks the robot to describe it. Number 5 begins by being very unimaginative and precise, describing the paper's chemical composition and things like this. The scientist laughs, thinking he has caught the robot out. But then Number 5 begins to describe the red smudge, saying it looks like a butterfly or a flower and flights of artistic fancy take over. The scientist becomes convinced that Number 5 is alive. I do not know if robots will ever be created that can think artistically or judge which of two things looks more beautiful than the other but I know that human beings can. And this common bond with other people that forms into culture is yet another background which free will needs in order to operate.

I do not think that there is any more reason to worry about a robot that would have free will than there is to worry about a person that has free will. It is not freedom to do anything that is scary anyway because that freedom never really exists. All choices are made against the backgrounds that make us and shape us in endless connections we could never count or quantify. And, what's more, our thinking is not so much done by us in a deliberative way as it is simply a part of our make up anyway. In this respect we act, perhaps, more like a computer in that we think and calculate just because that is what, once "switched on" with life, we will do. "More input!" as Number 5 said in Short Circuit. This is why we talk of thought occuring to us rather than us having to sit down and deliberate to produce thoughts in the first place. Indeed, it is still a mystery exactly how these things happen at all but we can say that thoughts just occur to us (without us seemingly doing anything but being a normal, living human being) as much, if not more, than that we sit down and deliberately create them. We breathe without thinking "I need to breathe" and we think without thinking "I need to think".

So, all my thinking these past few days about robots has, with nearly every thought I've had, forced me into thinking ever more closely about what it is to be human. I imagine the robot CHAPPiE, from the film of the same name, going from a machine made to look vaguely human to having that consciousness.dat program loaded into its memory for the first time. I imagine consciousness flooding the circuitry and I imagine that as a human. One minute you are nothing and the next this massive rush of awareness floods your consciousness, a thing you didn't even have a second before. To be honest, I am not sure how anything could survive that rush of consciousness. It is just such an overwhelmingly profound thing. I try to imagine my first moments as a baby emerging into the world. Of course, I can't remember what it was like. But I understand most babies cry and that makes sense to me. In CHAPPiE the robot is played as a child on the basis, I suppose, of human analogy. But imagine you had just been given consciousness for the first time, and assume you manage to get over that hurdle of being able to deal with the initial rush: how would you grow and develop then? What would your experience be like? Would the self-awareness be overpowering? (As someone who suffers from mental illness my self-awareness at times can be totally debilitating.) We traditionally protect children and educate them, recognising that they need time to grow into their skins, as it were. Would a robot be any different?

My thinking about robots has led to lots of questions and few answers. I write these blogs not as any kind of expert but merely as a thoughtful person. I think one conclusion I have reached is that what separates humans from all other beings, natural or artificial, at this point is SELF AWARENESS. Maybe you would also call this consciousness too. I'm not yet sure how we could meaningfully talk of an artificially intelligent robot having self-awareness. That's one that will require more thought. But we know, or at least assume, that we are the only natural animal on this planet, or even in the universe that we are aware of, that knows it is alive. Dogs don't know they are alive. Neither do whales, flies, fish, etc. But we do. And being self-aware and having a consciousness, being reasoning beings, is a lot of what makes us human. In the film AI, directed by Steven Spielberg, the opening scene shows the holy grail of robot builders to be a robot that can love. I wonder about this though. I like dogs and I've been privileged to own a few. I've cuddled and snuggled with them and that feels very like love. But, of course, our problem in all these things is that we are human. We are anthropocentric. We see with human eyes. This, indeed, is our limitation. And so we interpret the actions of animals in human ways. Can animals love? I don't know. But it looks a bit like it. In some of the robot films I have watched the characters develop affection for variously convincing humanoid-shaped lumps of metal. I found that more difficult to swallow. But we are primed to recognise and respond to cuteness. Why do you think the Internet is full of cat pictures? So the question remains: could we build an intelligent robot that could mimic all the triggers in our very human minds, that could convince us it was alive, self-aware, conscious? After all, it wouldn't need to actually BE any of these things. It would just need to get us to respond AS IF IT WAS!

My next blog will ask: Are human beings robots?

With this blog I'm releasing an album of music made as I thought about intelligent robots and used that to help me think about human beings. It's called ROBOT and its part 8 of my Human/Being series of albums. You can listen to it HERE!

Take "free will" for example. It is customary to regard free will as the freedom to act on your own recognisance without coercion or pressure from outside sources in any sense. But, when you think about it, free will is not free in any absolute sense at all. Besides the everyday circumstances of your life, which directly affect the choices you can make, there is also your genetic make up to consider. This affects the choices you can make too because it is responsible not just for who you are but who you can be. In short, there is both nature and nurture acting upon you at all times. What's more, you are one tiny piece of a chain of events, a stream of consciousness if you will, that you don't control. Some people would even suggest that things happen the way they do because they have to. Others, who believe in a multiverse, suggest that everything that can possibly happen is happening right now in a billion different versions of all possible worlds. Whether you believe that or not, the point is made that so much more happens in the world every day that you don't control than the tiny amount of things that you do.

And then we turn to robots. Robots are artificial creations. I've recently watched a number of films which toy with the fantasy that robots could become alive. As Number 5 in the film Short Circuit says, "I'm alive!". As creations, robots have a creator. They rely on the creator's programming to function. This programming delimits all the possibilities for the robot concerned. But there is a stumbling block. This stumbling block is called "artificial intelligence". Artificial Intelligence, or AI, is like putting a brain inside a robot (a computer in effect) which can learn and adapt in ways analogous to the human mind. This, it is hoped, allows the robot to begin making its own choices, developing its own thought patterns and ways of choosing. It gives the robot the ability to reason. It is a very moot point, for me at least, whether this would constitute the robot as being alive, as having a consciousness or as being self-aware. And would a robot that could reason through AI therefore have free will? Would that depend on the programmer or could such a robot "transcend its programming"?

Well, as I've already suggested, human free will it not really free. Human free will is constrained by many factors. But we can still call it free because it is the only sort of free will we could ever have anyway. Human beings are fallible and contingent beings. They are not gods and cannot stand outside the stream of events to get a view that wasn't a result of them or that will not have consequences further on down the line for them. So, in this respect, we could not say that a robot couldn't have free will because it would be reliant on programming or constrained by outside things - because all free will is constrained anyway. Discussing the various types of constraint and their impact is another discussion though. Here it is enough to point out that free will isn't free whether you are a human or an intelligent robot. Being programmed could act as the very constraint which makes robot free will possible, in fact.

It occurs to me as I write out this blog that one difference between humans and robots is culture. Humans have culture and even many micro-cultures and these greatly influence human thinking and action. Robots, on the other hand, have no culture because these things rely on sociability and being able to think and feel for yourself. Being able to reason, compare and pass imaginative, artistic judgments are part of this too. Again, in the film Short Circuit, the scientist portrayed by actor Steve Guttenberg refuses to believe that Number 5 is alive and so he tries to trick him. He gives him a piece of paper with writing on it and a red smudge along the fold of the paper. He asks the robot to describe it. Number 5 begins by being very unimaginative and precise, describing the paper's chemical composition and things like this. The scientist laughs, thinking he has caught the robot out. But then Number 5 begins to describe the red smudge, saying it looks like a butterfly or a flower and flights of artistic fancy take over. The scientist becomes convinced that Number 5 is alive. I do not know if robots will ever be created that can think artistically or judge which of two things looks more beautiful than the other but I know that human beings can. And this common bond with other people that forms into culture is yet another background which free will needs in order to operate.

I do not think that there is any more reason to worry about a robot that would have free will than there is to worry about a person that has free will. It is not freedom to do anything that is scary anyway because that freedom never really exists. All choices are made against the backgrounds that make us and shape us in endless connections we could never count or quantify. And, what's more, our thinking is not so much done by us in a deliberative way as it is simply a part of our make up anyway. In this respect we act, perhaps, more like a computer in that we think and calculate just because that is what, once "switched on" with life, we will do. "More input!" as Number 5 said in Short Circuit. This is why we talk of thought occuring to us rather than us having to sit down and deliberate to produce thoughts in the first place. Indeed, it is still a mystery exactly how these things happen at all but we can say that thoughts just occur to us (without us seemingly doing anything but being a normal, living human being) as much, if not more, than that we sit down and deliberately create them. We breathe without thinking "I need to breathe" and we think without thinking "I need to think".

So, all my thinking these past few days about robots has, with nearly every thought I've had, forced me into thinking ever more closely about what it is to be human. I imagine the robot CHAPPiE, from the film of the same name, going from a machine made to look vaguely human to having that consciousness.dat program loaded into its memory for the first time. I imagine consciousness flooding the circuitry and I imagine that as a human. One minute you are nothing and the next this massive rush of awareness floods your consciousness, a thing you didn't even have a second before. To be honest, I am not sure how anything could survive that rush of consciousness. It is just such an overwhelmingly profound thing. I try to imagine my first moments as a baby emerging into the world. Of course, I can't remember what it was like. But I understand most babies cry and that makes sense to me. In CHAPPiE the robot is played as a child on the basis, I suppose, of human analogy. But imagine you had just been given consciousness for the first time, and assume you manage to get over that hurdle of being able to deal with the initial rush: how would you grow and develop then? What would your experience be like? Would the self-awareness be overpowering? (As someone who suffers from mental illness my self-awareness at times can be totally debilitating.) We traditionally protect children and educate them, recognising that they need time to grow into their skins, as it were. Would a robot be any different?

My thinking about robots has led to lots of questions and few answers. I write these blogs not as any kind of expert but merely as a thoughtful person. I think one conclusion I have reached is that what separates humans from all other beings, natural or artificial, at this point is SELF AWARENESS. Maybe you would also call this consciousness too. I'm not yet sure how we could meaningfully talk of an artificially intelligent robot having self-awareness. That's one that will require more thought. But we know, or at least assume, that we are the only natural animal on this planet, or even in the universe that we are aware of, that knows it is alive. Dogs don't know they are alive. Neither do whales, flies, fish, etc. But we do. And being self-aware and having a consciousness, being reasoning beings, is a lot of what makes us human. In the film AI, directed by Steven Spielberg, the opening scene shows the holy grail of robot builders to be a robot that can love. I wonder about this though. I like dogs and I've been privileged to own a few. I've cuddled and snuggled with them and that feels very like love. But, of course, our problem in all these things is that we are human. We are anthropocentric. We see with human eyes. This, indeed, is our limitation. And so we interpret the actions of animals in human ways. Can animals love? I don't know. But it looks a bit like it. In some of the robot films I have watched the characters develop affection for variously convincing humanoid-shaped lumps of metal. I found that more difficult to swallow. But we are primed to recognise and respond to cuteness. Why do you think the Internet is full of cat pictures? So the question remains: could we build an intelligent robot that could mimic all the triggers in our very human minds, that could convince us it was alive, self-aware, conscious? After all, it wouldn't need to actually BE any of these things. It would just need to get us to respond AS IF IT WAS!

My next blog will ask: Are human beings robots?

With this blog I'm releasing an album of music made as I thought about intelligent robots and used that to help me think about human beings. It's called ROBOT and its part 8 of my Human/Being series of albums. You can listen to it HERE!

Labels:

AI,

artificial intelligence,

being,

Chappie,

existence,

existentialism,

films,

life,

movies,

personhood,

philosophy,

robots,

science fiction

Wednesday, 18 March 2015

Humans and Robots: Are They So Different?

Today I have watched the film "Chappie" from Neill Blomkamp, the South African director who also gave us District 9 and Elysium. Without going into too much detail on a film only released for two weeks, its a film about a military robot which gets damaged and is sent to be destroyed but is saved at the last moment when its whizzkid inventor saves it to try out his new AI program on it (consciousness.dat). What we get is a robot that becomes self-aware and develops a sense of personhood. For example, it realises that things, and it, can die (in its case when its battery runs out).

Of course, the idea of robot beings is not new. It is liberally salted throughout the history of the science fiction canon. So whether you want to talk about Terminators (The Terminator), Daleks (Doctor Who), Replicants (Bladerunner) or Transformers (Transformers), the idea that things that are mechanical or technological can think and feel like us (and sometimes not like us or "better" than us) is not a new one. Within another six weeks we will get another as the latest Avengers film is based around fighting the powerful AI robot, Ultron.

Watching Chappie raised a lot of issues for me. You will know if you have been following this blog or my music recently that questions of what it is to be human or to have "being" have been occupying my mind. Chappie is a film which deliberately interweaves such questions into its narrative and we are expressly meant to ask ourselves how we should regard this character as we watch the film, especially as various things happen to him or as he has various decisions to make. Is he a machine or is he becoming a person? What's the difference between those two? The ending to the film, which I won't give away here, leads to lots more questions about what it is that makes a being alive and what makes beings worthy of respect. These are very important questions which lead into all sorts of other areas such as human and animal rights and more philosophical questions such "what is it to be a person"? Can something made entirely of metal be a person? If not, then are we saying that only things made of flesh and bone can have personhood?

I can't but be fascinated by these things. For example, the film raises the question of if a consciousness could be transferred from one place to another. Would you still be the same "person" in that case? That, in turn, leads you to ask what a person is. Is it reducible to a "consciousness"? Aren't beings more than brain or energy patterns? Aren't beings actually physical things too (even a singular unity of components) and doesn't it matter which physical thing you are as to whether you are you or not? Aren't you, as a person, tied to your particular body as well? The mind or consciousness is not an independent thing free of all physical restraints. Each one is unique to its physical host. This idea comes to the fore once we start comparing robots, deliberately created and programmed entities, usually on a common template, with people. The analogy is often made in both directions so that people are seen as highly complicated computer programs and robots are seen as things striving to be something like us - especially when AI enters the equation. But could a robot powered by AI ever actually be "like a human"? Are robots and humans just less and more complicated versions of the same thing or is the analogy only good at the linguistic level, something not to be pushed further than this?

Besides raising philosophical questions of this kind its also a minefield of language. Chappie would be a him - indicating a person. Characters like Bumblebee in Transformers or Roy Batty in Bladerunner are also regarded as living beings worthy of dignity, life and respect. And yet these are all just more or less complicated forms of machine. They are metal and circuitry. Their emotions are programs. They are responding, all be it in very complicated ways, as they are programmed to respond. And yet we use human language of them and the film-makers try to trick us into having human emotions about them and seeing them "as people". But none of these things are people. Its a machine. What does it matter if we destroy it. We can't "kill" it because it was never really "alive", right? An "on/off" switch is not the same thing as being dead, surely? When Chappie talks about "dying" in the film it is because the military robot he is has a battery life of 5 days. He equates running out of power with being dead. If you were a self-aware machine I suppose this would very much be an existential issue for you. (Roy Batty, of course, is doing what he does in Bladerunner because replicants have a hard-wired lifespan of 4 years.) But then turn it the other way. Aren't human beings biological machines that need fuel to turn into energy so that they can function? Isn't that really just the same thing?

There are just so many questions here. Here's one: What is a person? The question matters because we treat things we regard as like us differently to things that we don't. Animal Rights people think that we should protect animals from harm and abuse because in a number of cases we suggest they can think and feel in ways analogous to ours. Some would say that if something can feel pain then it should be protected from having to suffer it. That seems to be "programmed in" to us. We have an impulse against letting things be hurt and a protecting instinct. And yet there is something here that we are forgetting about human beings that sets them apart from both animals and most intelligent robots as science fiction portrays them. This is that human beings can deliberately do things that will harm them. Human beings can set out to do things that are dangerous to themselves. Now animals, most would say, are not capable of doing either good or bad because we do not judge them self-aware enough to have a conscience and so be capable of moral judgment or of weighing up good and bad choices. We do not credit them with the intelligence to make intelligent, reasoned decisions. Most robots or AI's that have been thought of always have protocols about not only protecting themselves from harm but (usually) humans too as well. Thus, we often get the "programming gone wrong" stories where robots become killing machines. But the point there is that that was never the intention when these things were made.

So human beings are not like either animals or artificial lifeforms in this respect because, to be blunt, human beings can be stupid. They can harm themselves, they can make bad choices. And that seems to be an irreducible part of being a human being: the capacity for stupidity. But humans are also individuals. We differentiate ourselves one from another and value greatly that separation. How different would one robot with AI be from another, identical, robot with an identical AI? Its a question to think about. How about if you could collect up all that you are in your mind, your consciousness, thoughts, feelings, memories, and transfer them to a new body, one that would be much more long lasting. Would you still be you or would something irreducible about you have been taken away? Would you actually have been changed and, if so, so what? This question is very pertinent to me as I suffer from mental illness which, more and more as it is studied, is coming to be seen as having hereditary components. My mother, too, suffers from a similar thing as does her twin sister. It also seems as if my brother's son might be developing a similar thing too. So the body I have, and the DNA that makes it up, is something very personal to me. It makes me who I am and has quite literally shaped my experience of life and my sense of identity. Changing my body would quite literally make me a different person, one without certain genetic or biological components. Wouldn't it?

So many questions. But this is only my initial thoughts on the subject and I'm sure they will be on-going. So you can expect that I will return to this theme again soon. Thanks for reading!

You can hear my music made whilst I was thinking about what it is to be human here!

Of course, the idea of robot beings is not new. It is liberally salted throughout the history of the science fiction canon. So whether you want to talk about Terminators (The Terminator), Daleks (Doctor Who), Replicants (Bladerunner) or Transformers (Transformers), the idea that things that are mechanical or technological can think and feel like us (and sometimes not like us or "better" than us) is not a new one. Within another six weeks we will get another as the latest Avengers film is based around fighting the powerful AI robot, Ultron.

Watching Chappie raised a lot of issues for me. You will know if you have been following this blog or my music recently that questions of what it is to be human or to have "being" have been occupying my mind. Chappie is a film which deliberately interweaves such questions into its narrative and we are expressly meant to ask ourselves how we should regard this character as we watch the film, especially as various things happen to him or as he has various decisions to make. Is he a machine or is he becoming a person? What's the difference between those two? The ending to the film, which I won't give away here, leads to lots more questions about what it is that makes a being alive and what makes beings worthy of respect. These are very important questions which lead into all sorts of other areas such as human and animal rights and more philosophical questions such "what is it to be a person"? Can something made entirely of metal be a person? If not, then are we saying that only things made of flesh and bone can have personhood?

I can't but be fascinated by these things. For example, the film raises the question of if a consciousness could be transferred from one place to another. Would you still be the same "person" in that case? That, in turn, leads you to ask what a person is. Is it reducible to a "consciousness"? Aren't beings more than brain or energy patterns? Aren't beings actually physical things too (even a singular unity of components) and doesn't it matter which physical thing you are as to whether you are you or not? Aren't you, as a person, tied to your particular body as well? The mind or consciousness is not an independent thing free of all physical restraints. Each one is unique to its physical host. This idea comes to the fore once we start comparing robots, deliberately created and programmed entities, usually on a common template, with people. The analogy is often made in both directions so that people are seen as highly complicated computer programs and robots are seen as things striving to be something like us - especially when AI enters the equation. But could a robot powered by AI ever actually be "like a human"? Are robots and humans just less and more complicated versions of the same thing or is the analogy only good at the linguistic level, something not to be pushed further than this?

Besides raising philosophical questions of this kind its also a minefield of language. Chappie would be a him - indicating a person. Characters like Bumblebee in Transformers or Roy Batty in Bladerunner are also regarded as living beings worthy of dignity, life and respect. And yet these are all just more or less complicated forms of machine. They are metal and circuitry. Their emotions are programs. They are responding, all be it in very complicated ways, as they are programmed to respond. And yet we use human language of them and the film-makers try to trick us into having human emotions about them and seeing them "as people". But none of these things are people. Its a machine. What does it matter if we destroy it. We can't "kill" it because it was never really "alive", right? An "on/off" switch is not the same thing as being dead, surely? When Chappie talks about "dying" in the film it is because the military robot he is has a battery life of 5 days. He equates running out of power with being dead. If you were a self-aware machine I suppose this would very much be an existential issue for you. (Roy Batty, of course, is doing what he does in Bladerunner because replicants have a hard-wired lifespan of 4 years.) But then turn it the other way. Aren't human beings biological machines that need fuel to turn into energy so that they can function? Isn't that really just the same thing?

There are just so many questions here. Here's one: What is a person? The question matters because we treat things we regard as like us differently to things that we don't. Animal Rights people think that we should protect animals from harm and abuse because in a number of cases we suggest they can think and feel in ways analogous to ours. Some would say that if something can feel pain then it should be protected from having to suffer it. That seems to be "programmed in" to us. We have an impulse against letting things be hurt and a protecting instinct. And yet there is something here that we are forgetting about human beings that sets them apart from both animals and most intelligent robots as science fiction portrays them. This is that human beings can deliberately do things that will harm them. Human beings can set out to do things that are dangerous to themselves. Now animals, most would say, are not capable of doing either good or bad because we do not judge them self-aware enough to have a conscience and so be capable of moral judgment or of weighing up good and bad choices. We do not credit them with the intelligence to make intelligent, reasoned decisions. Most robots or AI's that have been thought of always have protocols about not only protecting themselves from harm but (usually) humans too as well. Thus, we often get the "programming gone wrong" stories where robots become killing machines. But the point there is that that was never the intention when these things were made.

So human beings are not like either animals or artificial lifeforms in this respect because, to be blunt, human beings can be stupid. They can harm themselves, they can make bad choices. And that seems to be an irreducible part of being a human being: the capacity for stupidity. But humans are also individuals. We differentiate ourselves one from another and value greatly that separation. How different would one robot with AI be from another, identical, robot with an identical AI? Its a question to think about. How about if you could collect up all that you are in your mind, your consciousness, thoughts, feelings, memories, and transfer them to a new body, one that would be much more long lasting. Would you still be you or would something irreducible about you have been taken away? Would you actually have been changed and, if so, so what? This question is very pertinent to me as I suffer from mental illness which, more and more as it is studied, is coming to be seen as having hereditary components. My mother, too, suffers from a similar thing as does her twin sister. It also seems as if my brother's son might be developing a similar thing too. So the body I have, and the DNA that makes it up, is something very personal to me. It makes me who I am and has quite literally shaped my experience of life and my sense of identity. Changing my body would quite literally make me a different person, one without certain genetic or biological components. Wouldn't it?

So many questions. But this is only my initial thoughts on the subject and I'm sure they will be on-going. So you can expect that I will return to this theme again soon. Thanks for reading!

You can hear my music made whilst I was thinking about what it is to be human here!

Labels:

being,

Bladerunner,

Chappie,

Daleks,

death,

Doctor Who,

existence,

existentialism,

films,

human,

humanity,

meaning,

movies,

personhood,

philosophy,

science fiction,

Transformers,

Ultron

Friday, 13 March 2015

Insights from The German Music Progressives

I spent last night watching various documentaries on You Tube about the progressive German music of the early 1970s. This was the music detrimentally referred to as "Krautrock" by the British music press but also known as progressive, "space rock" or, my preferred term, Kosmische Musik. It encompasses bands such as Tangerine Dream, Can, Kraftwerk, Cluster, Neu!, Faust and Amon Düül II (plus many others).

A number of things struck me watching these documentaries and I thought I would write a few words about this.

The first was that the music, as a movement (and it wasn't a movement, its a purely heuristic move to put these and other bands under a label), comes in a historical context. All these bands were formed by people living after the Second World War in a defeated country that had been occupied by other forces. The capital city itself, Berlin, was partitioned. The music of this time in Germany was conservative and non-threatening (known, in German, as Schlager, a form of music once championed by Goebbels). It was also the time, in the late 60s, of student uprisings, not just in Germany but across the world. The time was ripe for striking out in a new way and differentiating yourself from the world of the past.

It had never occurred to me before that just in the act of making music you are actually being very political. In one of the films I watched, Dieter Moebius, one half of Cluster as well as a member of Harmonia and part of a double act on some work with legendary German producer, Conny Plank, stated that Schlager was not at all political - which made it political. In other places the music came from politics, such as the Munich commune which gave birth to both Amon Düül and Amon Düül II. Even Edgar Froese, who sadly died recently, can be seen in a documentary about the birth of this music saying that progressive German acts of the time didn't want to sound like American or British music. In places like the pioneering Zodiac Free Arts Lab in the Kreuzberg district of Berlin (a place I'm thrilled to have lived very near to in the recent past although the club is long since gone) like-minded people could get together and just jam and forge a new path.

So the question is, if you don't want to sound like the dominant musical tropes of your time (clearly a political move) then what do you do? Edgar Froese's reply was: be abstract. For many of the others it was: use synthesizers or electronics, new instruments just being born at that time. For some the guitars so reminiscent of American blues or British beat music just had to be ditched. This interests me greatly. I wonder how many people even set out with the idea to sound a certain way or give thought to the consequences of how they sound. I also wonder how many realise that "how they sound" could be being judged in this way. For myself, I've always wanted to sound like me and I've always been against purposely setting out to sound like someone else. For me, the worst thing I can find is that musicians or groups advertise themselves as sounding like someone else. Documentaries like the ones I watched last night reinforce this view in me and even extend it. To set out to fit into a trend or be like the mainstream is a deeply conservative act. I don't want to be conservative. And neither did they. So, a follow up question becomes "What does the music you make say about you?"

Many of the acts associated with Kosmische Musik were experimental. Often they were also electronic and abstract, although not always so. If we try and find links between them we see this wanting to forge a new path, to not be linked to the past but to chart a course for a different future, as something that binds them together. It is not the music of mass culture and indeed, in the early 70s, many of these bands were largely unknown in their own country and sometimes not even known to each other. People did later try to mass market some of the bands that came from this era but few were very successful. It also struck me how much so many of the people involved were deep thinkers and this thinking led on voyages of discovery. This could be the esoteric rambling of Can over a funky backbeat supplied by legendary drummer, Jaki Liebezeit, or the experiments in electronic abstraction of Cluster, Klaus Schulze and Tangerine Dream. Many of these acts were about messing around which electronic equipment of various kinds (as had been done by John Cage, Pierre Schaefer and Karl-Heinz Stockhausen, amongst others, in the 50s and 60s) and using sounds made from every day items. One film I watched had two members of Faust making a song by hitting and recording various parts of a cement mixer, for example, as well as playing it rhythmically as a rudimentary drum. To me, this unites a desire to be different with an "art of the possible" mentality.

Perhaps the two most widely known bands from this era now are Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream. They are both, in their way, examples of something that Faust member, Jean-Hervé Péron, said in one of the films I watched: "Art is living. Living is art. Life is art." Tangerine Dream's output was massive with over 100 albums to their name in a career lasting around 45 years. Kraftwerk have been much less prolific but their music, as with so many of the other German progressives, is very much an expression of their beliefs and mentality. "There is no separation between humans and technology, for us they belong together", says Ralf Hütter, one of Kraftwerk's founders and the only surviving founder member of the band. So when they say "We are the robots" they actually mean it. Their music is a physical expression, an embodiment, of their actual beliefs. And if you go through the bands who were "kosmische" you find this repeated again and again. The music is an embodiment of the people making it. It turns thought into its physical expression putting flesh on the bones of who they are. It is, in a way, musical autobiography.

So why does this interest me? Because I have found myself in exactly the same place. For me, music is a deeply intellectual and philosophical enterprise. Its not merely having fun (though, of course, it always should be about fun). The music I make is deeply and unalterably about identity and it seems that for the German progressives of the early 70s it was too. Like them, I don't want to sound like anyone else either. Like them, I have thought about what I sound like from the outside looking in. Like them, I have tried to not do what is expected of me. Like them, for me these are important considerations. Music is not just some product you try to produce for money. You are not trying to find a place in the music supermarket for your particular brand of baked beans. Music is art. Life is art. Art is life. I may be 45 years too late (in truth, kosmische was being born about exactly at the same time as I physically was) but I do feel that in kosmische I have found a musical place I can call home.

Postscript

Here are 3 kosmische albums I've been playing non-stop for the last 4 or 5 months

1. Yeti by Amon Düül II

2. Zuckerzeit by Cluster

3. Affenstunde by Popol Vuh

I also made my own attempt at Kosmische Musik (actually its more "music influenced by listening to Kosmische Musik") with the help of two friends, Luke Clarke and Valerie Polichar. "Shikantaza" can be heard here---> SHIKANTAZA