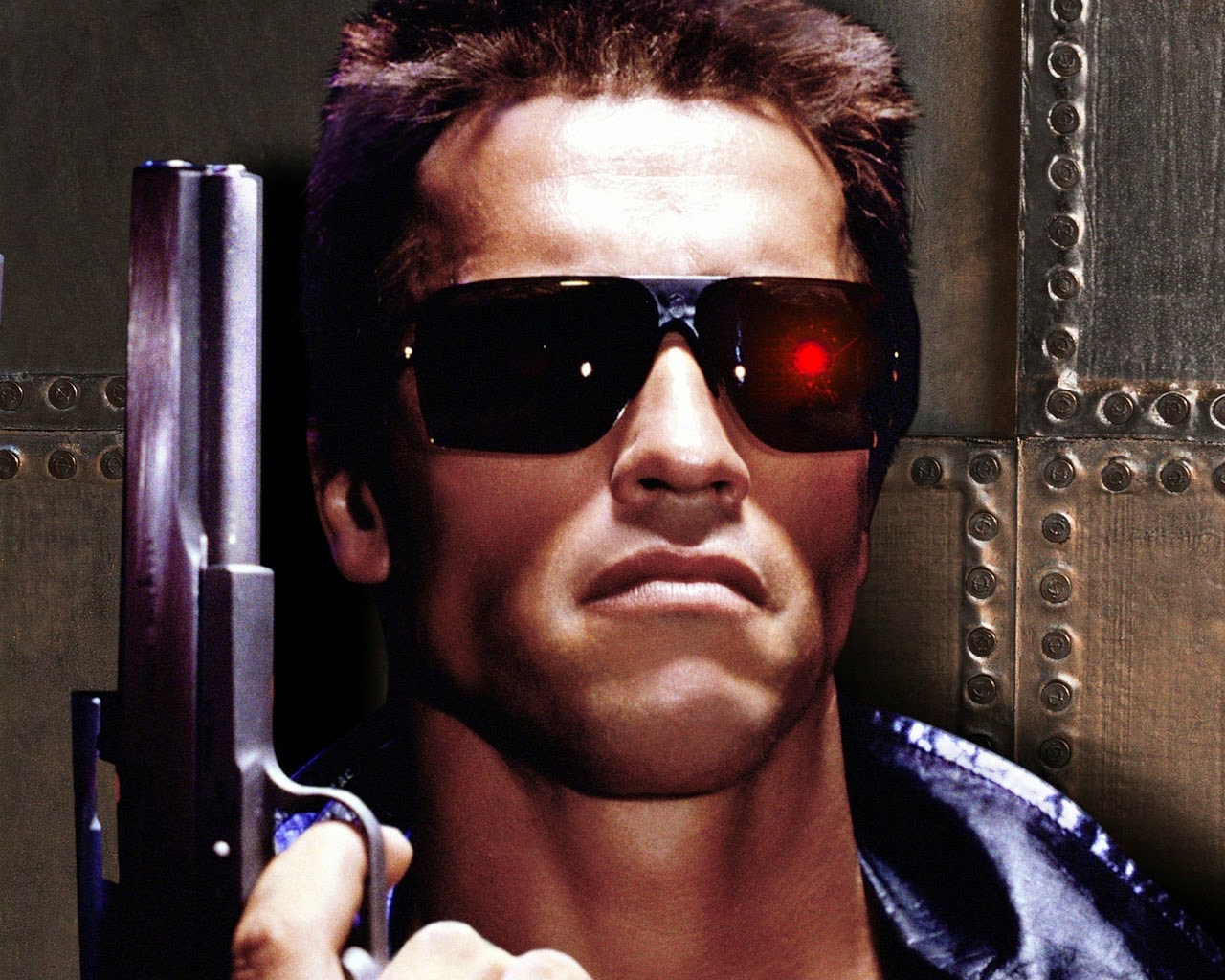

There is a scene near the beginning of classic science fiction film Blade Runner where our hero, Deckard, played by Harrison Ford, has gone to the headquarters of the Tyrell Corporation to meet its head, Eldon Tyrell. He is met there by a stunningly beautiful assistant called Rachael. Deckard is there to perform tests on the employees to discover if any might be replicants, synthetic beings created by the Tyrell Corporation, some of which have rebelled and become dangerous to humans. Specifically, he needs to know if the tests he has available to him will work on the new Nexus 6 type replicants that have escaped. Tyrell wants to see Deckard perform his tests on a test subject before he allows the tests to continue. Deckard asks for such a test subject and Tyrell suggests Rachael. The test being completed, Tyrell asks Rachael to step outside for a moment. Deckard suggests that Rachael is a replicant and Tyrell confirms this and that she is not aware of it. “How can it not know what it is?” replies a bemused Deckard.

This question, in the wider context of the film and the history of its reception, is ironic. Blade Runner was not a massively popular film at the time of its cinematic release and was thought to have underperformed. But, over the years, it has become a classic, often placed in the top three science fiction films ever made. That popularity and focus on it as a serious film of the genre has, in turn, produced an engaged fan community. One issue regarding the film has always been the status of Deckard himself. Could it be that Deckard was himself a replicant? Interestingly, those involved with the production of the film have differing views.

Back in 2002 the director, Ridley Scott, confirmed that, for him, Deckard was indeed a replicant and that he had made the film in such a way as this was made explicit. However, screenwriter Hampton Fancher, who wrote the basic plot of the film, does not agree with this. For him the question of Deckard’s status must forever stay mysterious and in question. It should be forever “an eternal question” that “doesn’t have an answer”. Interestingly, for Harrison Ford Deckard was, and always should be, a human. Ford has stated that this was his main area of contention with Ridley Scott when making the film. Ford believed that the viewing audience needed at least one human on the screen “to build an emotional relationship with”. Finally, in Philip K. Dick’s original story, on which Blade Runner is based, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Deckard is a human. At this point I playfully need to ask how can they not agree what it is?

Of course, in the context of the film Deckard’s question now takes on a new level of meaning. Deckard is asking straightforwardly about the status of Rachael while, perhaps, having no idea himself what he is. The irony should not be lost on us. But let us take the question and apply it more widely. Indeed, let’s turn it around and put it again: how can he know what he is? This question is very relevant and it applies to us too. How can we know what we are? We see a world around us with numerous forms of life upon it and, we would assume, most if not all of them have no idea what they are. And so it comes to be the case that actually knowing what you are would be very unusual if not unique. “How can it not know what it is?” starts to look like a very naive question (even though Deckard takes it for granted that Rachael should know and assumes that he does of himself). But if you could know you would be the exception not the rule.

I was enjoying a walk yesterday evening and, as usual, it set my mind to thinking going through the process of the walk. My mind settled on the subject of Fibromyalgia, a medical condition often characterised by chronic widespread pain and a heightened and painful response to pressure. Symptoms other than pain may occur, however, from unexplained sweats, headaches and tingling to muscle spasms, sleep disturbance and fatigue. (There are a host of other things besides.) The cause of this condition is unknown but Fibromyalgia is frequently associated with psychiatric conditions such as depression and anxiety and among its causes are believed to be psychological and neurobiological factors. One simple thesis is that in vulnerable individuals psychological stress or illness can cause abnormalities in inflammatory and stress pathways which regulate mood and pain. This leads to the widespread symptoms then evidenced. Essentially, certain neurons in the brain are set “too high” and trigger physical responses. Or, to put it another way more suitable to my point here, the brain is the cause of the issues it then registers as a problem.

The problem here is that the brain does not know that it was some part of itself that caused the issue in the first place. It is just an unexplained physical symptom being registered as far as it is concerned. If the brain was aware and conscious surely it would know that some part of it was the problem? But the brain is not conscious: “I” am. It was at this point in my walk that I stopped and laughed to myself at the absurdity of this. “I” am conscious. Not only did I laugh at the notion of consciousness and what it might be but I also laughed at this notion of the “I”. What do I mean when I say “I”? What is this “I”? And that was when the question popped into my head: how can it not know what it is?

The question is very on point. If I was to say to you right now that you were merely a puppet, some character in a divinely created show for the amusement of some evil god you couldn’t prove me wrong. Because you may be. If I was to say that you are a character in some future computer game a thousand years from now you couldn’t prove me wrong either. Because, again, you could be. How you feel about it and what you think you know notwithstanding. Because we know that there are limits to our knowledge and we know that it is easy to fool a human being. We have neither the knowledge nor the capacity for the knowledge to feel even remotely sure that we know what we are or what “I” might refer to. We have merely comforting notions which help us to get by, something far from the level of insight required to start being sure.

“How can it not know what it is?” now seems almost to be a very dumb question. “How can it know what it is?” now seems much more relevant and important. For how can we know? Of course Rachael didn’t know what she was. That is to be normal. We, in the normal course of our lives, gain a sense of self and our place in the world and this is enough for us. We never strive for ultimate answers (because, like Deckard, we already think we know) and, to be frank, we do not have the resources for it anyway. Who we think we are is always enough and anything else is beyond our pay grade. Deckard, then, is an “everyman” in Blade Runner, one who finds security in what he knows he knows yet really doesn’t know. It enables him to get through the day and perform his function. It enables him to function. He is a reminder that this “I” is always both a presence and an absence, both there and yet not. He is a reminder that who we are is always a “feels to be” and never yet an “is”. Subjectivity abounds.

How can it not know what it is? How, indeed, could it know?

This article is a foretaste of a multimedia project I am currently producing called "Mind Games". The finished project will include written articles, an album of music and pictures. It should be available in a few weeks.

This article is a foretaste of a multimedia project I am currently producing called "Mind Games". The finished project will include written articles, an album of music and pictures. It should be available in a few weeks.